- Home

- Therapeutic area

- Thrombosis

Venous Thromboembolism (VTE)

The prevalence of VTE in Africa is high following surgery, in pregnancy and postpartum.1 At least one quarter of patients at risk of VTE in Africa are not receiving prophylaxis.2 VTE includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT), when a blood clot forms in a deep vein, usually in the leg and pulmonary embolism (PE), when the clot breaks off and travels from the leg up to the lungs.3 DVT and PE are serious, life-threatening conditions that require immediate medical attention.

-

1. Epidemiology of VTE

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) occurs for the first time in ≈100 persons per 100,000 each year in the United States and rises exponentially from <5 cases per 100,000 persons <15 years old to ≈500 cases (0.5%) per 100,000 persons at age 80 years4. Approximately one third of patients with symptomatic VTE manifest pulmonary embolism (PE), whereas two thirds manifest deep vein thrombosis (DVT) alone.4 Despite anticoagulant therapy, VTE recurs frequently in the first few months after the initial event, with a recurrence rate of ≈7% at 6 months. Death occurs in ≈6% of DVT cases and 12% of PE cases within 1 month of diagnosis4. The time of year may affect the occurrence of VTE, with a higher incidence in the winter than in the summer. One major risk factor for VTE is ethnicity, with a significantly higher incidence among Caucasians and African Americans than among Hispanic persons and Asian-Pacific Islanders.4 Overall, ≈25% to 50% of patient with first-time VTE have an idiopathic condition, without a readily identifiable risk factor. Early mortality after VTE is strongly associated with presentation as PE, advanced age, cancer, and underlying cardiovascular disease.4

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) may not be a common medical presentation in most hospitals in Ghana, however, it can cause serious medical complications and mortality if its diagnosis and subsequent treatment are overlooked or underestimated.5 1 in 3 hospitalized patients are at risk for Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) therefore health professionals must see it and treat it as a medical emergency with all the severity it deserves.5

-

2. Pathophysiology 6

A thrombus is a solid mass composed of platelets and fibrin with a few trapped red and white blood cells that forms within a blood vessel. Hypercoagulability or obstruction leads to the formation of a thrombus in the deep veins of the legs, pelvis, or arms.

As the clot propagates, proximal extension occurs, which may dislodge or fragment and embolize to the pulmonary arteries. This causes pulmonary artery obstruction, and the release of vasoactive agents (ie, serotonin) by platelets increases pulmonary vascular resistance. The arterial obstruction increases alveolar dead space and leads to redistribution of blood flow, thus impairing gas exchange due to the creation of low ventilation-perfusion areas within the lung.

The increased pulmonary vascular resistance causes an increase in right ventricular afterload, and tension rises in the right ventricular wall, which may lead to dilatation, dysfunction, and ischemia of the right ventricle. Right heart failure can occur and lead to cardiogenic shock and even death.

-

3. Etiology of VTE

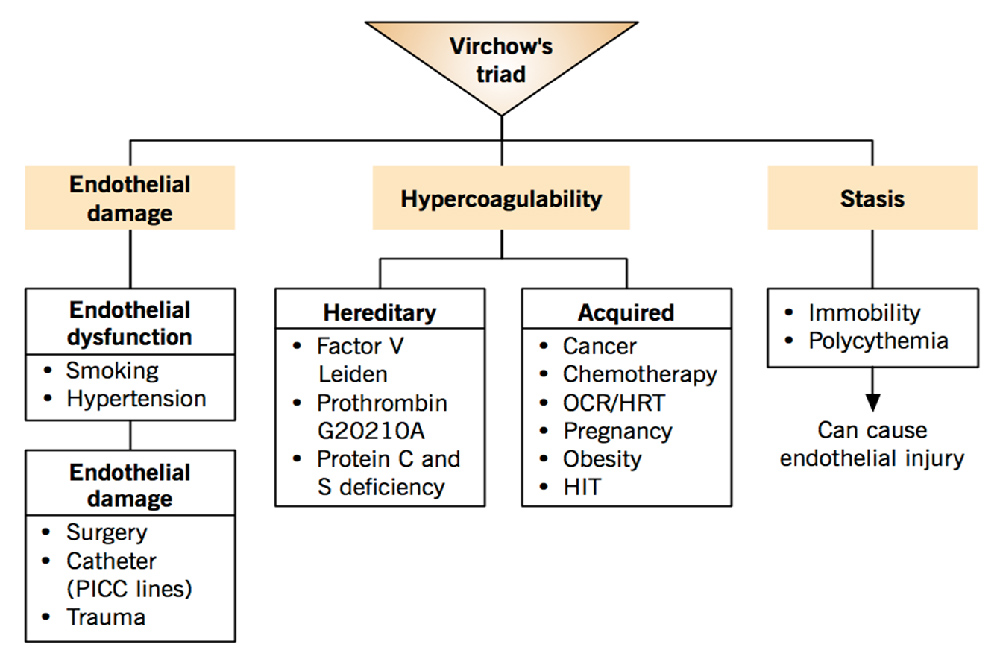

Figure 1: Source: McMaster Pathophysiology Review; Etiology of Venous Thrombo-Embolism Available at: http://www.pathophys.org/vte/pe-virchow-2/ Etiology 6

Risk factors for thromboembolic disease can be divided into a number of categories, including patient-related factors, disease states, surgical factors, and hematologic disorders. Risk is additive.

- Patient-related factors include age older than 40 years, obesity, varicose veins, the use of estrogen in pharmacologic doses (ie, oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy), and immobility.

- Disease states such as malignancy, congestive heart failure, nephrotic syndrome, recent myocardial infarction, inflammatory bowel disease, spinal cord injury with paralysis, and pelvic, hip, or long-bone fracture confer increased risk of thromboembolic disease.

- Surgical factors are related to procedure type and procedure duration. Among patients who have undergone hip surgery, 50% have a proximal DVT on the same side as the hip surgery. This is thought to be due to a twisting of the femoral vein during total hip replacement. The incidence of DVT is higher in patients who have undergone knee surgery.7

- In a study of patients following pelvic surgery, 40-80% had calf DVT, and 10-20% had thigh vein thromboses. Fatal PE developed in 1-5% of patients. The risk for thromboembolic disease has been shown to be increased with coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), urologic surgery, and neurosurgery.8

One study identified the following four risk factors as being highly predictive of VTE among hospitalized medical patients, these four-element risk assessment model, was accurate at identifying patients at risk of developing VTE within 90 days and was more effective than the Kucher Score, a risk assessment score.9

- Previous VTE

- An order for bed rest

- Peripherally inserted central venous catheterization line

- Cancer diagnosis

Hematologic disorders that increase thromboembolic risk include the following:6

- Activated protein C resistance (factor V Leiden)

- Protein C or protein S deficiency

- Antithrombin III deficiency

- Lupus anticoagulant

- Polycythemia vera

- Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

- Dysfibrinogenemia

- Prothrombin mutation

-

4. Clinical Features of VTE

Signs and symptoms 6

Signs and symptoms of thromboembolism include the following:

- Acute onset of shortness of breath; dyspnea is the most frequent symptom of PE

- Pleuritic chest pain, cough, or hemoptysis (with a smaller PE near the pleura)

- Syncope (with a massive PE)

- Sense of impending doom, with apprehension and anxiety

- Complaints related to signs of DVT, lower extremity swelling, and warmth to touch or tenderness

- Tachypnea (respiratory rate >18 breaths/min)

- Tachycardia

- Accentuated second heart sound

- Fever

- Normal findings from lung examination

- Cyanosis

Diagnosis 6

Workup for thromboembolism includes the following:

- Pulmonary angiography: Diagnostic standard for PE

- Ventilation-perfusion scanning: Most common screening technique

- Venography: Standard test for validating new diagnostic procedures

- Arterial blood gas values on room air: Hypoxemia, elevated alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient

- Acid-base status: Respiratory alkalosis

- Enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) for D-dimer

- Electrocardiography, especially for ruling out myocardial infarction

- Chest radiography: Most often normal but occasionally suggestive

- Helical (spiral) computed tomography of pulmonary vessels

- Doppler ultrasonography of venous system

- Echocardiography

- Impedance plethysmography: Of limited value when DVT is asymptomatic or distal or when findings are nonocclusive

-

5. Risk factors and risk assessment

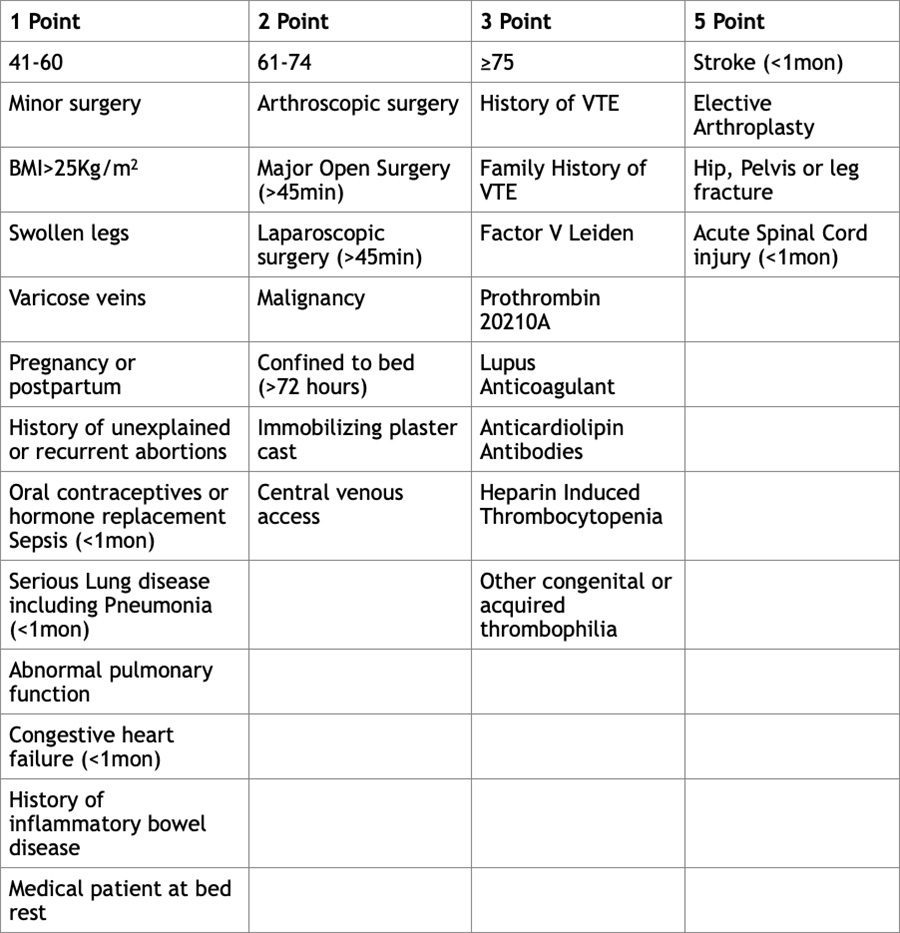

The table above is the Cabrini risk assessment tool.

The importance/role of hospitalization

VTE can result from three pathogenic mechanisms: hypercoagulability (increased tendency of blood to clot), stasis or slow blood flow, and vascular injury to blood vessel walls. Hospitalization is an important risk factor in the latter two mechanisms; injury and surgery are causes of vascular injury, and prolonged bed rest can cause stasis. Approximately half of new VTE cases occur during a hospital stay or within 90 days of an inpatient admission or surgical procedure, and many are not diagnosed until after discharge.10

National Institute of Clinical Excellence (nice) risk assessment & the need for VTE prophylaxis

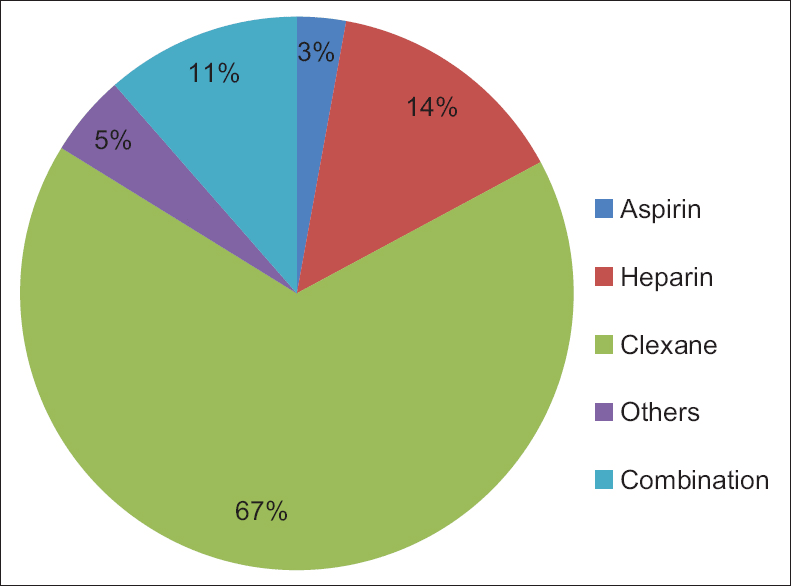

Below are the results of a survey on prophylaxis of DVT amongst Nigerian surgeons, published in 2016 13

The pie charts above shows the Pharmacological and Mechanical agents of choice in thromboprophylaxis carried out in 8 Nigerian university hospitals13

The study concluded that “there is a deficiency in the knowledge and practice of DVT prophylaxis among surgeons in Nigeria. There is a need to improve both the knowledge and practice by introducing institutional guidelines or protocol for DVT prophylaxis for surgical patients”.

For Medical and Surgical Patients:

The National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends physicians assess all medical, surgical and trauma patients to identify the risk of VTE and bleeding as soon as possible after admission to hospital or by the time of the first consultant review. The Physician should balance the person's individual risk of VTE against their risk of bleeding when deciding whether to offer pharmacological thromboprophylaxis to medical patients.

If using pharmacological VTE prophylaxis for any of the above patient groups, start it as soon as possible and within 14 hours of admission, unless otherwise stated in the population-specific recommendations.

For Pregnant Women:

Assess all women on admission to hospital or a midwife-led unit if they are pregnant or gave birth, had a miscarriage or had a termination of pregnancy in the past 6 weeks, to identify their risk of VTE and bleeding. Use a tool published by a national UK body, professional network or peer-reviewed journal.

-

6. Management of VTE 6

Anticoagulant and thrombolytic therapy options are available for the treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Anticoagulant therapy prevents further clot deposition and allows the patient’s natural fibrinolytic mechanisms to lyse the existing clot.

Anticoagulant Therapy 6

Anticoagulant inpatient medications should include heparin or a low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), followed by the initiation of an oral coumarin derivative. The predominant coumarin derivative in clinical use in North America is warfarin sodium.

The anticoagulant properties of unfractionated heparin (UFH), LMWH, and warfarin sodium stem from their effects on the factors and cofactors of the coagulation cascade.

Patients with acute, massive pulmonary embolism (PE) causing hemodynamic instability may be treated initially with a thrombolytic agent (eg, tissue plasminogen activator [t-PA]). t-PA has increasingly been used as the first-choice thrombolytic agent.

Heparin

Heparin is the first line of therapy. It is administered by bolus dosing, followed by a continuous infusion. Adequacy of therapy is determined by an activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) of 1.5-2 times baseline. Progression or recurrence of thromboembolism is 15 times more likely when a therapeutic aPTT is not achieved within the first 48 hours.

The goal is to achieve an international normalized ratio (INR) of 2.0-3.0. The optimum duration of treatment depends on several factors (eg, first episode or recurrent event, other underlying risk factors). A minimum of 3 months of oral therapy has been suggested following a first episode of DVT or PE.

Low-molecular-weight heparin

Several studies have shown that LMWH, which is a fractionated heparin, is as effective as UFH in treating DVT.

Factor Xa and direct thrombin inhibitors

Apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, and betrixaban are alternatives to warfarin for prophylaxis or treatment of DVT and PE. Apixaban, edoxaban, rivaroxaban, and betrixaban all inhibit factor Xa, whereas dabigatran is a direct thrombin inhibitor.

Thrombolytic Therapy 6

Thrombolytic therapy dissolves recent clots promptly by activating a plasma proenzyme, plasminogen, to its active form, plasmin. Plasmin degrades fibrin to soluble peptides. Thrombolytic therapy speeds pulmonary tissue reperfusion and rapidly reverses right heart failure. It also improves pulmonary capillary blood flow and more rapidly improves hemodynamic parameters.

The recombinant t-PAs (rt-PAs) tenecteplase, alteplase, and reteplase are thrombolytic agents that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved for thrombolytic use in PE. In head-to-head studies by Goldhaber et al between rt-PA and heparin, there was a higher incidence of recurrent PE and death in the group receiving heparin.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (nice) recommendations 12

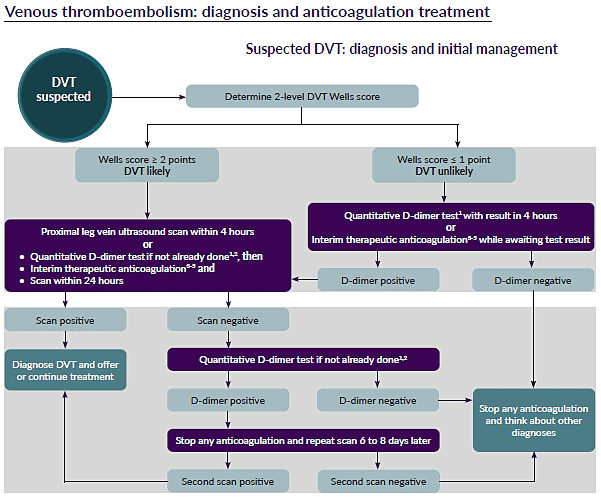

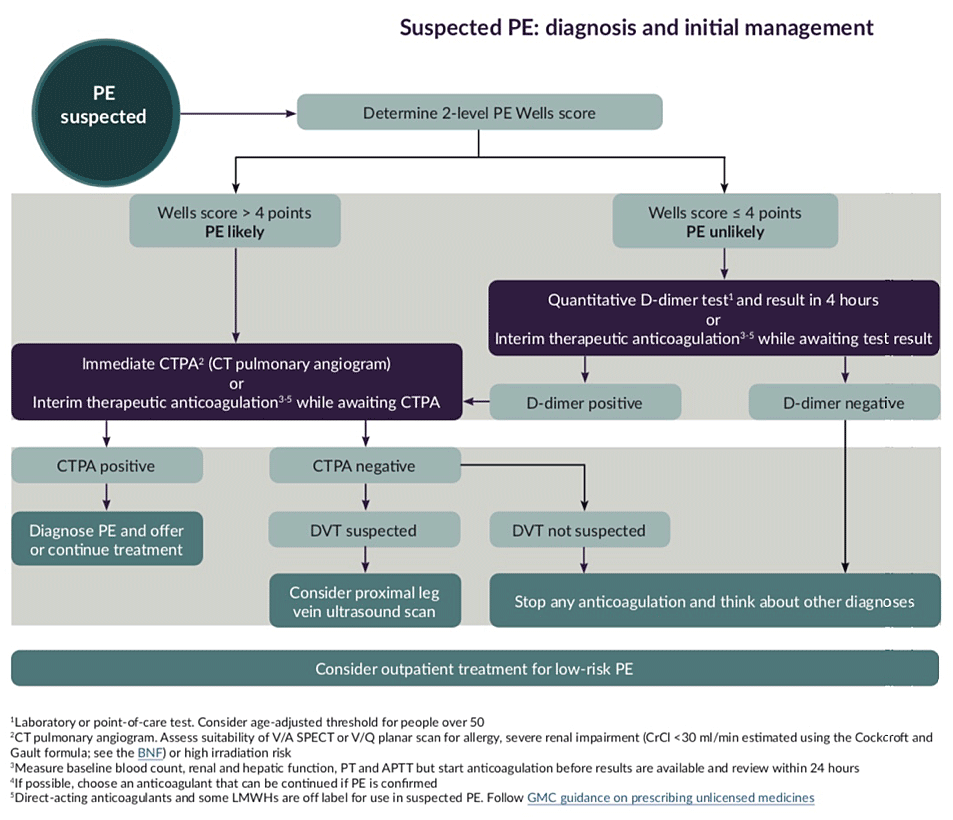

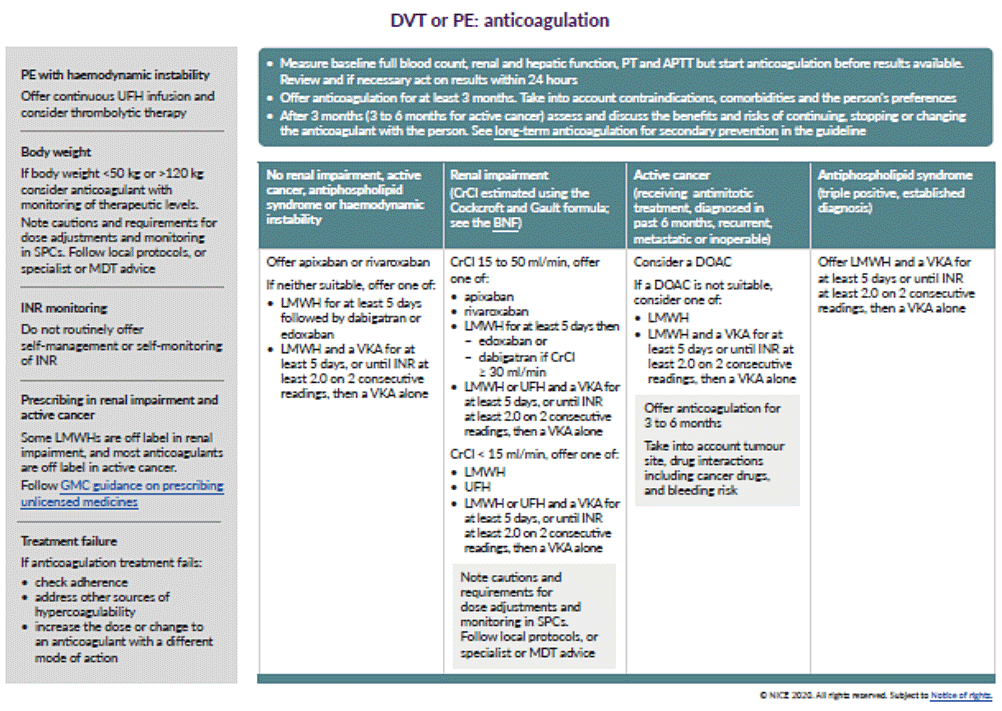

NICE recommends that therapeutic anticoagulation should be initiated immediately, preferably with a LMWH, fondaparinux, rivaroxaban, or UFH (see Figure 2, 3 & 4 below).

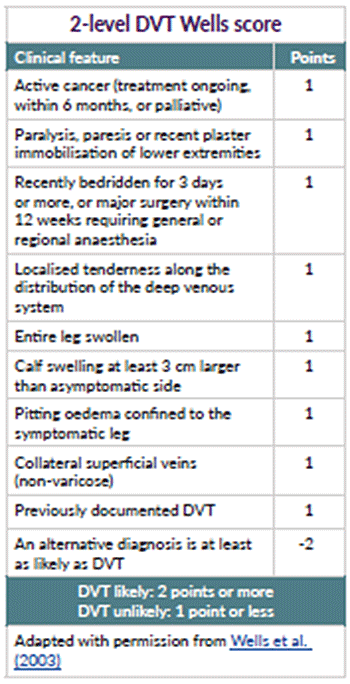

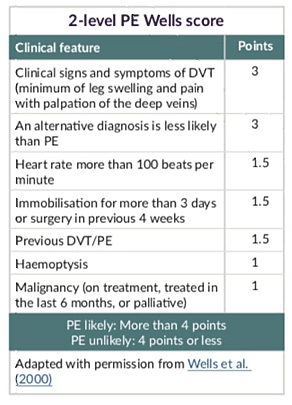

Figure 2: Source: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng158/resources/visual-summary-pdf-8709091453

Figure 3: Source: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng158/resources/visual-summary-pdf-8709091453

Figure 4: Source: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng158/resources/visual-summary-pdf-8709091453 -

7. References

- Kingue S, Bakilo L, Ze Minkande J, Fifen I, Gureja Y, Razafimahandry HJ, et al.(2014) Epidemiological African day for evaluation of patients at risk of venous thrombosis in acute hospital care settings. Cardiovasc J Afr.25:159-64.

- Morrissey,J.H and Lillicrap,D. (Ed.).(2020).The International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 18(7): 1538-7836.Retrived from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/15387836

- Mayo (1998).Deep Vein Thrombolisis (DVT).Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/deep-vein-thrombosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20352557

- White RH.(2003).The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(23 Suppl 1): I4-I8.

- Anane, Charles & Kuffour, Angela & Ama, Nana. (2010). Deep Vein Thrombosis-A Case Study Presentation in a Teaching Hospital in Ghana. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225089252_Deep_Vein_Thrombosis-A_Case_Study_Presentation_in_a_Teaching_Hospital_in_Ghana

- De Palo V.A. Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) Medscape Reference. Updated Oct. 2019 Available at: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1267714-overview Accessed July 15, 2020

- Khokhar A, Chari A, Murray D, McNally M, Pandit H. Venous thromboembolism and its prophylaxis in elective knee arthroplasty: an international perspective. Knee. 2013 Jun. 20 (3):170-6.

- Attaya H, Wysokinski WE, Bower T, Litin S, Daniels PR, Slusser J, et al. Three-month cumulative incidence of thromboembolism and bleeding after periprocedural anticoagulation management of arterial vascular bypass patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2013 Jan. 35 (1):100-6.

- Woller SC, Stevens SM, Jones JP, Lloyd JF, Evans RS, Aston VT, et al. Derivation and validation of a simple model to identify venous thromboembolism risk in medical patients. Am J Med. 2011 Oct. 124 (10):947-954.e2.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) CDC Grand Rounds: Preventing Hospital-Associated Venous Thromboembolism. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6309a3.htm Accessed July 24, 2020

- Venous thromboembolism in over 16s: Reducing the risk of hospital-acquired deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. NICE guideline [NG89]Published date: 2018 updated: 13 August 2019 Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng89/chapter/Recommendations#interventions-for-pregnant-women-and-women-who-gave-birth-or-had-a-miscarriage-or-termination-of Accessed July 24, 2020

- [Guideline] Venous thromboembolism: diagnosis and anticoagulation treatment. NICE March 2020. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng158/resources/visual-summary-pdf-8709091453 Accessed on July 24, 2020

- Kesieme E B, Arekhandia B J, Inuwa I M, Akpayak I C, Ekpe E E, Olawoye O A, Umar A, Awunor N S, Amadi E C, Ofoegbu I J. Knowledge and practice of prophylaxis of deep venous thrombosis: A survey among Nigerian surgeons. Niger J Clin Pract 2016;19:170-4

MAT-NG-2000084 | October 2020