- Home

- Therapeutic area

- Cardiovascular

Hypertension Therapeutic Area

-

1. Overview/Epidemiology

Cardiovascular diseases were the leading cause of death in Africa in 2017, being responsible for 1.42 million deaths in that year or 16.4% of the total deaths in all ages compared with 11.3% of total deaths in 1990.1 The mortality represents a 61.0% increase over the estimated number of cardiovascular deaths in 1990. High systolic blood pressure (SBP) accounted for nearly two-thirds of the cardiovascular deaths in Africa in 2017.1 Sadly, the World Health Organization (WHO) African Region has the highest prevalence of hypertension in the world (27%).2

In 2019, Okubadejo et al. carried out a population-based survey in Lagos, Nigeria and their reported prevalence of hypertension was 55.0% and 27.5% based on the ACC/AHA 2017 guideline and the JNC7 2003 guidelines respectively.3 The prevalence of hypertension in Nigeria however varies between children and adults, men and women and urban vs rural dwelling. This is evident by a 2015 systematic review which reports a overall crude prevalence of hypertension ranging from 0.1% to 17.5% in children and 2.1% to 47.2% in adults depending on the benchmark used for diagnosis of hypertension, crude prevalence of hypertension ranged from 6.2% to 48.9% for men and 10% to 47.3% for women with most studies, prevalence of hypertension was higher in males than females. The prevalence across urban and rural ranged from 9.5% to 51.6% and 4.8% to 43% respectively.4

Similar findings were reported in a systematic review in Ghana where the prevalence of hypertension (BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg ± antihypertensive treatment) ranged from 19% to 48% between studies. Sex differences were generally minimal and urban populations tended to have higher prevalence than rural population in studies with mixed population types.5

-

2. Pathophysiology and risk factors of hypertension

Hypertension may be primary, which may develop as a result of environmental or genetic causes, or secondary, which has multiple etiologies, including renal, vascular, and endocrine causes. Primary or essential hypertension accounts for 90-95% of adult cases, and secondary hypertension accounts for 2-10% of cases.6

The pathogenesis of essential hypertension is multifactorial and complex. Multiple factors modulate the blood pressure (BP) including humoral mediators, vascular reactivity, circulating blood volume, vascular caliber, blood viscosity, cardiac output, blood vessel elasticity, and neural stimulation.6 It is probable that many interrelated factors contribute to the raised blood pressure in hypertensive patients, and their relative roles may differ between individuals. Among the factors that have been intensively studied are salt intake, obesity and insulin resistance, the renin-angiotensin system, and the sympathetic nervous system. Other factors evaluated, include genetics, endothelial dysfunction (as manifested by changes in endothelin and nitric oxide), low birth weight and intrauterine nutrition, and neurovascular anomalies.7

Blood pressure is determined by the cardiac output balanced against systemic vascular resistance. The process of maintaining blood pressure is complex, and involves numerous physiological mechanisms, including arterial baroreceptors, the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, atrial natriuretic peptide, endothelins, and mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid steroids. Together, these complex systems manage the degree of vasodilatation or vasoconstriction within the systemic circulation, and the retention or excretion of sodium and water, to maintain an adequate circulating blood volume.8

Dysfunction in any of these processes can lead to the development of hypertension. This may be through increased cardiac output, increased systemic vascular resistance, or both.8

Blood vessels become less elastic and more rigid as patients age, which reduces vasodilatation and increases systemic vascular resistance, leading to a higher systolic blood pressure (often with a normal diastolic pressure). In contrast, hypertension in younger patients tends to be associated with increased cardiac output, which can be caused by environmental or genetic factors.8

Risk Factors for Hypertension are Summarized in Table 1 Below

Modifiable Risk Factors* Relatively Fixed Risk Factors ** Current cigarette smoking, secondhand smoking CKD

Family historyDiabetes mellitus Increased age Dyslipidemia/hypercholesterolemia Low socioeconomic/educational status Overweight/obesity Male sex Physical inactivity/low fitness Obstructive sleep apnea Unhealthy diet Psychosocial stress *Factors that can be changed and, if changed, may reduce CVD risk.

**Factors that are difficult to change (CKD, low socioeconomic/educational status, obstructive sleep apnea), cannot be changed (family history, increased age, male sex), or, if changed through the use of current intervention techniques, may not reduce CVD risk (psychosocial stress).

CKD indicates chronic kidney disease; and CVD, cardiovascular disease.Causes of secondary hypertension varies and have different pathogenesis 6

- Renal causes (2.5-6%) (e.g. Polycystic kidney disease, Chronic kidney disease, Urinary tract obstruction, Renin-producing tumor)

- Endocrine causes account for 1-2% and include exogenous or endogenous hormonal imbalances. Exogenous causes include administration of steroids. Endogenous causes include Primary hyperaldosteronism, Cushing syndrome, Pheochromocytoma, Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

- Renovascular (coexistence of renal arterial & vascular disease) hypertension (RVHT) causes 0.2-4% of cases e.g. Coarctation of aorta

- Drugs and toxins that cause hypertension include the following: Alcohol, Cocaine, Cyclosporine, tacrolimus, NSAIDs, Erythropoietin, Adrenergic medications, Decongestants containing ephedrine

-

3. Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Hypertension is diagnosed after an elevated blood pressure (BP) on at least three separate occasions (based on the average of 2 or more readings taken at each of ≥2 follow-up visits after initial screening)6 This diagnosis should include a detailed history which should extract the following information: Extent of end-organ damage (e.g. heart, brain, kidneys, eyes), assessment of patients’ cardiovascular risk status and exclusion of secondary causes of hypertension.

For Primary Hypertension, recommendations of the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7), the classification of BP for adults aged 18 years or older has been as follows:9

- Normal: Systolic lower than 120 mm Hg, diastolic lower than 80 mm Hg;

- Prehypertension: Systolic 120-139 mm Hg, diastolic 80-89 mm Hg;

- Stage 1: Systolic 140-159 mm Hg, diastolic 90-99 mm Hg;

- Stage 2: Systolic 160 mm Hg or greater, diastolic 100 mm Hg or greater.

The 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines10 eliminate the classification of prehypertension and divides it into two levels:

- Elevated BP, with a systolic pressure (SBP) between 120- and 129-mm Hg and diastolic pressure (DBP) less than 80 mm Hg, and

- stage 1 hypertension, with an SBP of 130 to 139 mm Hg or a DBP of 80 to 89 mm Hg.

Blood pressure categories in the new ACC/AHA guideline are:

- Normal: Less than 120/80 mm Hg;

- Elevated: Systolic between 120-129 and diastolic less than 80;

- Stage 1: Systolic between 130-139 or diastolic between 80-89;

- Stage 2: Systolic at least 140 or diastolic at least 90 mm Hg.

NICE Guideline Classification of Hypertension 11

- Stage 1 hypertension: Clinic blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg to 159/99 mmHg and subsequent ABPM daytime average or HBPM average blood pressure ranging from 135/85 mmHg to 149/94 mmHg;

- Stage 2 hypertension: Clinic blood pressure of 160/100 mmHg or higher but less than 180/120 mmHg and subsequent ABPM daytime average or HBPM average blood pressure of 150/95 mmHg or higher;

- Stage 3 or severe hypertension: Clinic systolic blood pressure of 180 mmHg or higher or clinic diastolic blood pressure of 120 mmHg or higher;

- Masked hypertension: Clinic blood pressure measurements are normal (less than 140/90 mmHg), but blood pressure measurements are higher when taken outside the clinic using average daytime ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) or average home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) blood pressure measurements;

- White-coat effect: A discrepancy of more than 20/10 mmHg between clinic and average daytime ABPM or average HBPM blood pressure measurements at the time of diagnosis.

Baseline Laboratory Evaluation

Initial laboratory tests may include urinalysis; fasting blood glucose or A1c; hematocrit; serum sodium, potassium, creatinine (estimated or measured glomerular filtration rate [GFR]), and calcium; and lipid profile following a 9- to 12-hour fast (total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein [LDL] cholesterol, and triglycerides). An increase in cardiovascular risk is associated with a decreased GFR level and with albuminuria.9 Other investigations is based on history obtained.

-

4. Management of hypertension

Many guidelines exist for the management of hypertension. Most groups, including the JNC, the American Diabetes Associate (ADA), and the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) recommend lifestyle modification as the first step in managing hypertension. (Medscape reference)

- The AHA/ASA recommends a diet that is low in sodium, is high in potassium, and promotes the consumption of fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products for reducing BP and lowering the risk of stroke. Other recommendations include increasing physical activity (30 minutes or more of moderate intensity activity daily) and losing weight (for overweight and obese persons).

- The 2018 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) guidelines recommend a low-sodium diet (limited to 2 g per day) as well as reducing body-mass index (BMI) to 20-25 kg/m2 and waist circumference (to < 94 cm in men and < 80 cm in women).12

Below in Table 2 is a summary of NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL approaches to control of the blood pressure

Nonpharmacological Intervention Approximate Impact on SBP Dose Hypertension Normotension Weight loss Weight/body fat Best goal is ideal body weight but aim for at least a 1-kg reduction in body weight for most adults who are overweight. Expect about 1 mm Hg for every 1-kg reduction in body weight. −5 mm Hg −2/3 mm Hg Healthy diet DASH dietary pattern Consume a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat dairy products, with reduced content of saturated and total fat. −11 mm Hg −3 mm Hg Reduced intake of dietary sodium Dietary sodium Optimal goal is <1500 mg/d but aim for at least a 1000-mg/d reduction in most adults. −5/6 mm Hg −2/3 mm Hg Enhanced intake of dietary potassium Dietary potassium Aim for 3500–5000 mg/d, preferably by consumption of a diet rich in potassium. −4/5 mm Hg −2 mm Hg Physical activity Aerobic 90–150 min/wk65%–75% heart rate reserve −5/8 mm Hg −2/4 mm Hg Dynamic resistance 90–150 min/wk50%–80% 1 rep maximum6 exercises, 3 sets/exercise, 10 repetitions/set −4 mm Hg −2 mm Hg Isometric resistance 4 × 2 min (hand grip), 1 min rest between exercises, 30%–40% maximum voluntary contraction, 3 sessions/wk8–10 wk −5 mm Hg −4 mm Hg Moderation in alcohol intake Alcohol consumption In individuals who drink alcohol, reduce alcohol† to: Men: ≤2 drinks daily Women: ≤1 drink daily −4 mm Hg −3 mm Hg DASH indicates Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension; and SBP, systolic blood pressure. Source: 2017 ACC/AHA Clinical Practice Guideline

Pharmacological Management of Hypertension

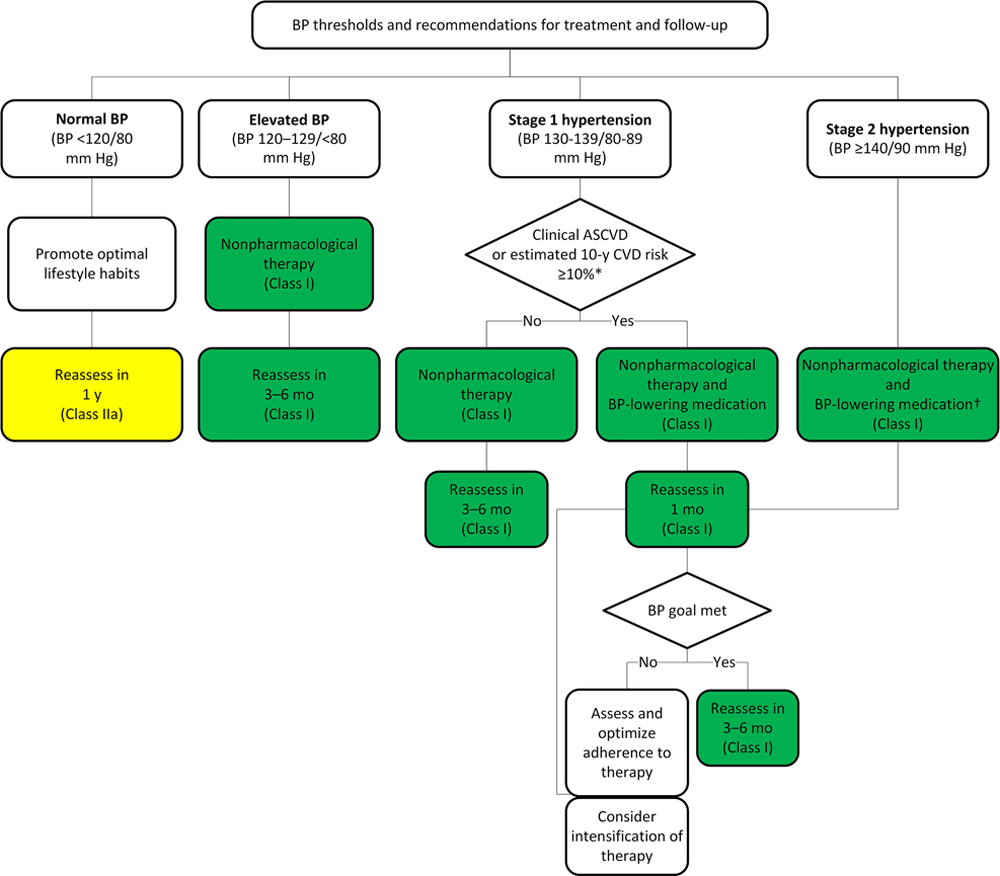

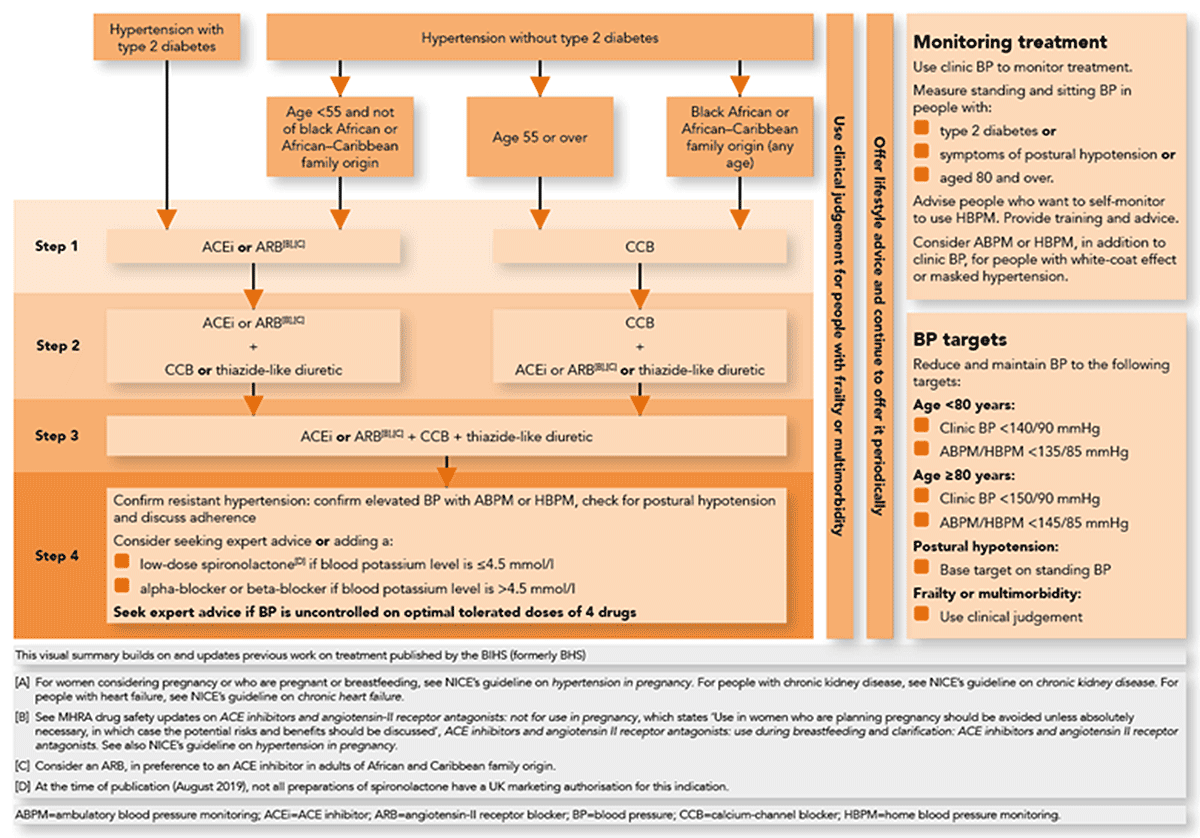

Figure 1 Hypertension ± ASCVD. Source: 2017 ACC/AHA Clinical Practice Guideline If lifestyle modifications are insufficient to achieve the goal BP, there are several drug options for treating and managing hypertension. Thiazide diuretics, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) /angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), or calcium channel blocker (CCB) are the preferred agents in nonblack populations, whereas CCBs or thiazide diuretics are favored in black hypertensive populations.13 These recommendations do not exclude the use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs in treatment of black patients, or CCBs or diuretics in non-black persons. Often, patients require several antihypertensive agents to achieve adequate BP control.13

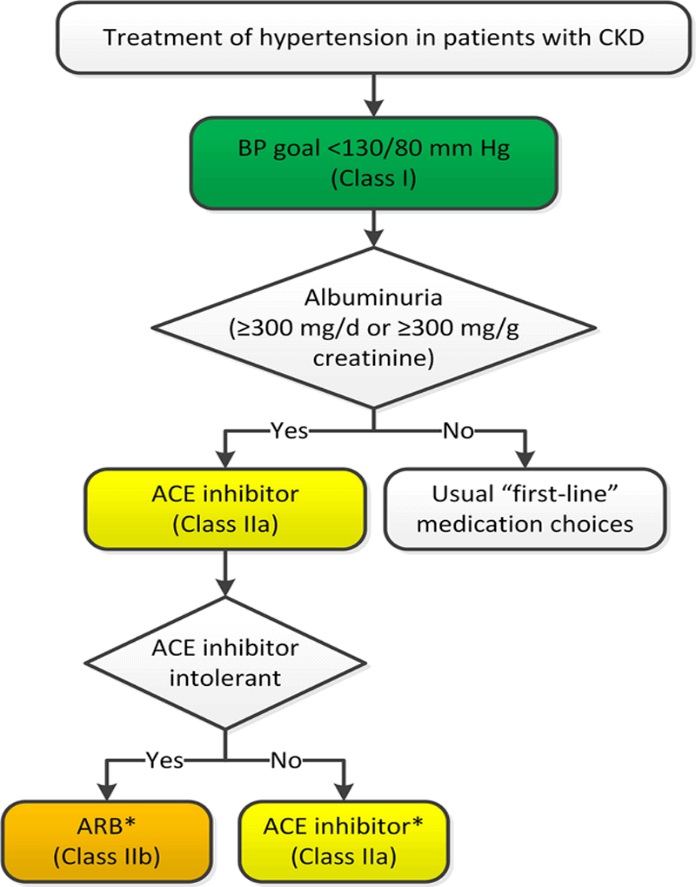

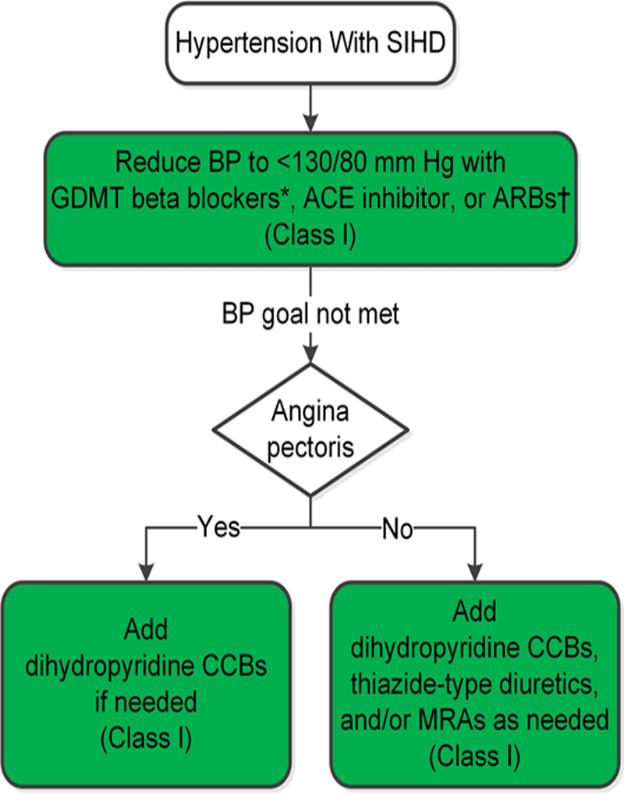

Special conditions such as Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD), Artherosclerotic Cardio-Vascular Disease (ASCVD), Stable Ischaemic Heart Disease (SIHD) etc., have specific recommendations on which antihypertensive agents to achieve desired outcomes (See Figure 1 Above and Figures 2 & 3 Below)

The following are drug class recommendations for compelling indications based on various clinical trials9- Heart failure: Diuretic, beta-blocker, ACE inhibitor/ARB, aldosterone antagonist

- Following myocardial infarction: Beta-blocker, ACE inhibitor

- Diabetes: ACE inhibitor/ARB

- Chronic kidney disease: ACE inhibitor/ARB

Figure 2: Hypertension with CKD

Figure 3: Hypertension with SIDH Source: 2017 ACC/AHA Clinical Practice Guideline

Selection of antihypertensive agents

Figure 4: NICE Guideline on choice of antihypertensive agents 11 Prognosis

Most individuals diagnosed with hypertension will have increasing blood pressure (BP) as they age. Untreated hypertension is notorious for increasing the risk of mortality and is often described as a silent killer. Mild to moderate hypertension, if left untreated, may be associated with a risk of atherosclerotic disease in 30% of people and organ damage in 50% of people within 8-10 years after onset. Patients with resistant hypertension are also at higher risk for poor outcomes, particularly those with certain comorbidities (e.g. chronic kidney disease, ischemic heart disease)14

Death from ischemic heart disease or stroke increases progressively as BP increases. For every 20 mm Hg systolic or 10 mm Hg diastolic increase in BP above 115/75 mm Hg, the mortality rate for both ischemic heart disease and stroke doubles.9

The Framingham Heart Study found a 72% increase in the risk of all-cause death and a 57% increase in the risk of any cardiovascular event in patients with hypertension who were also diagnosed with diabetes mellitus.15

-

5. References

- Bosu, W.K., Aheto, J.M.K., Zucchelli, E. et al. Determinants of systemic hypertension in older adults in Africa: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 19, 173 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-019-1147-7

- Hypertension. World Health Organization updated September 2019. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension Accessed June 7, 2020

- Okubadejo, N.U., Ozoh, O.B., Ojo, O.O. et al. Prevalence of hypertension and blood pressure profile amongst urban-dwelling adults in Nigeria: a comparative analysis based on recent guideline recommendations. Clin Hypertens 25, 7 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40885-019-0112-1

- Akinlua JT, Meakin R, Umar AM, Freemantle N. Current Prevalence Pattern of Hypertension in Nigeria: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2015 Oct 13;10(10):e0140021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140021.

- Bosu, W.K. Epidemic of hypertension in Ghana: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 10, 418 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-418

- Alexander M.R. et al. Hypertension. Medscape Reference updated February 2019. Available at: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/241381-overview Accessed June 7, 2020

- Beevers G, Lip GY, O'Brien E. ABC of hypertension: The pathophysiology of hypertension. BMJ. 2001 Apr 14;322(7291):912-6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7291.912.

- Williams H. Hypertension: pathophysiology and diagnosis. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2015; Available at: https://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/cpd-and-learning/cpd-article/hypertension-pathophysiology-and-diagnosis/20067718.cpdarticle?firstPass=false Accessed on June 7 2020

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003 Dec. 42(6):1206-52.

- [Guideline] Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018 Jun. 71(6): e13-e115.

- [Guideline] Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. NICE updated October 2019. Available at: https://www.guidelines.co.uk/cardiovascular/nice-hypertension-guideline/454934.article Accessed June 2020

- [Guideline] Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al, for the ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018 Sep 1. 39 (33):3021-104.

- [Guideline] James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014 Feb 5. 311 (5):507-20.

- [Guideline] Carey RM, Calhoun DA, et al. Resistant hypertension: detection, evaluation, and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2018 Nov. 72 (5):e53-e90.

- Chen G, McAlister FA, Walker RL, Hemmelgarn BR, Campbell NR. Cardiovascular outcomes in Framingham participants with diabetes: the importance of blood pressure. Hypertension. 2011 May. 57(5):891-7.

MAT-NG-2000034 | July 2020